In almost sixteen years of public work on the Bible, I have often been asked for an in-depth analysis of the Book of Enoch. Or rather, of the books of Enoch, because—it bears repeating—there is no single homogeneous “book,” but a complex, layered corpus, written in different periods, by different authors, with different perspectives and even different calendars.

So today I want to take you with me on a journey into that ancient, mysterious, and layered text: the Book of Enoch. Or, more precisely, the books of Enoch, because what we usually refer to as a single book is actually a composite corpus, built up over centuries and consisting of five main sections: The Book of the Watchers, The Book of Giants (largely lost and replaced by the Parables), The Book of Dreams, The Book of Astronomy, and The Epistle of Enoch.

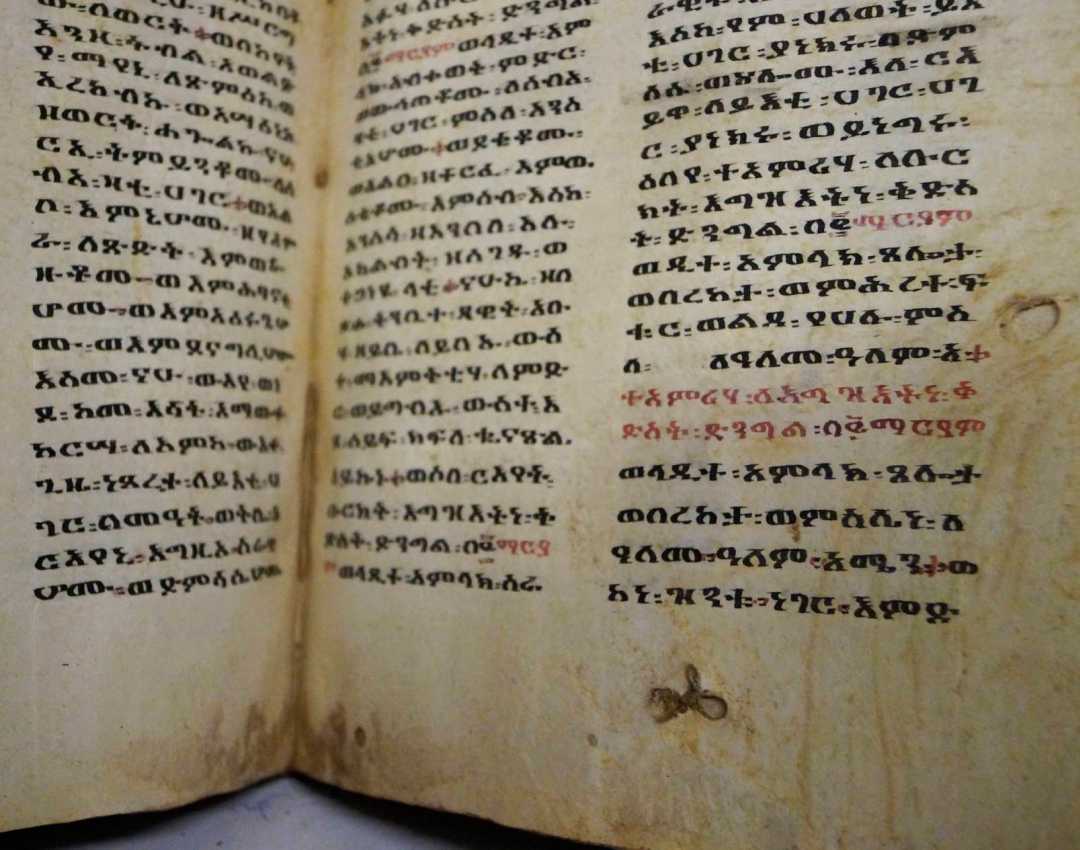

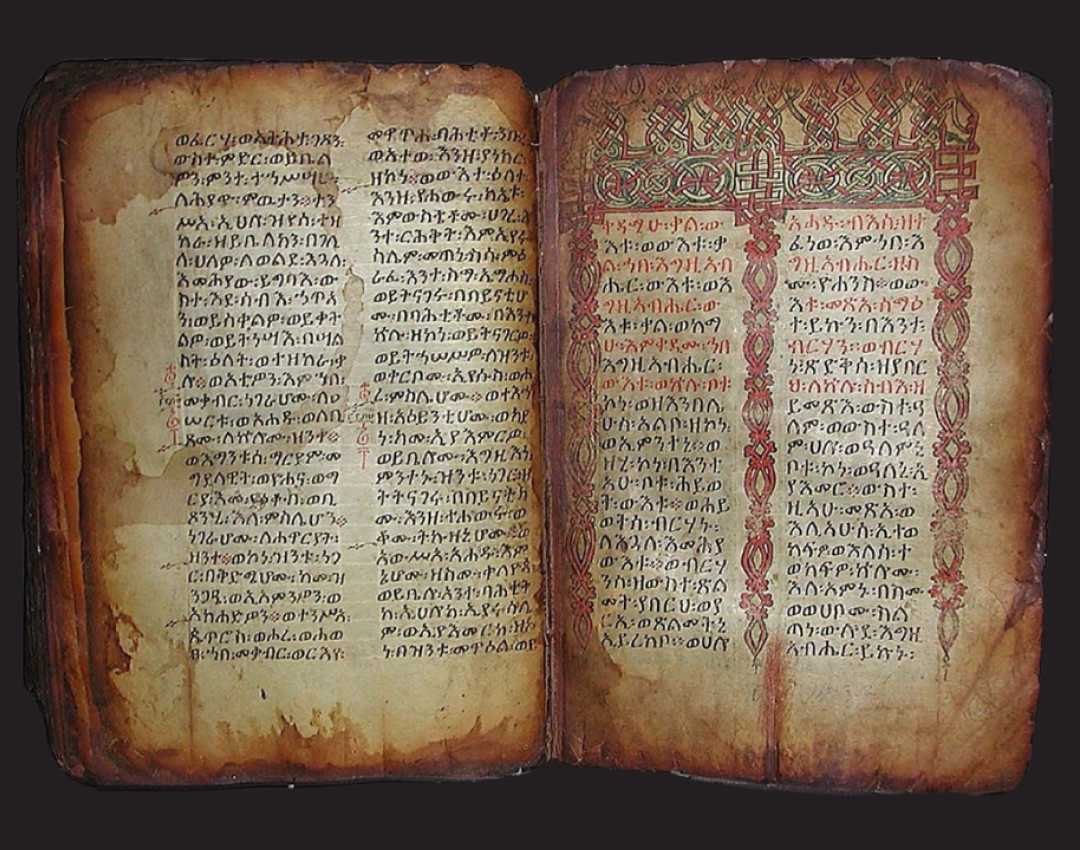

This collection, also known as the Enochic Pentateuch, has come down to us in its complete form only in Ge’ez, the ancient sacred language of Ethiopia, now dead but still used in Coptic liturgy. It is precisely the literal translation from Ge’ez that I have chosen to use: a rigorous version that allows us to work as closely as possible to the original text, while remaining aware of the numerous problems associated with manuscript transmission. (translated by Luigi Fusella, UTET, 2013, Turin, edited by Paolo Sacchi)

A fragmentary tradition and uncertain transmission

The Ge’ez text has come down to us through numerous copies made by scribes, with all the errors that this entails: marginal glosses that ended up in the body of the text, minor graphic variations that completely alter the meaning, passages that can no longer be traced with certainty to direct or indirect speech.

In addition, there is an Amharic translation (the national language of Ethiopia) commissioned by Emperor Haile Selassie, which often complicates the reading rather than clarifying it. The translator himself warns us that in many places the Amharic “follows” the Ge’ez without really understanding its meaning. All this requires a careful, contextual, and philologically sound reading.

Not a book but a corpus of books

When we refer to the “Book of Enoch” in the West, we usually mean 1 Enoch, which has been handed down in its entirety only in Ge’ez, the ancient sacred language of Ethiopia. In reality, 1 Enoch, as mentioned above, is a pentateuch—a five-part collection that, perhaps deliberately, echoes the structure of the Hebrew Torah:

- The Book of the Watchers (chapters 1-36)

- The Book of Giants, replaced in later times by the Book of Parables (chapters 37-71)

- The Book of Astronomy or of the Heavenly Luminaries (chapters 72-82)

- The Book of Dreams (chapters 83-90)

- The Epistle of Enoch (chapters 91-108)

To these five are added, in a separate tradition, 2 Enoch (Slavic) and, much later, 3 Enoch (Hebrew), which we should actually call Sefer Hechalot.

This overlap of titles, languages, and traditions already raises a fundamental problem: we are not dealing with a single work. Each book has its own purpose, author, lexicon, and date: at best, they range from the fifth century BC to the entire first century AD, a period of half a millennium in which Israel went from being a Persian province to an Hasmonean kingdom, then a vassal of Rome, until the destruction of the Temple. It is not surprising that theology changed, that sensibilities evolved, that political enemies disguised themselves as apocalyptic figures.

The multiple dates of composition of 1 Enoch

- The Book of the Watchers is the oldest: Aramaic fragments from Qumran date it to at least the first half of the 2nd century BC, but some themes suggest the 3rd century.

- The Book of Astronomy also appears at Qumran (4Q208-211) and may date back to the decades immediately preceding the Seleucid rise, perhaps the end of the third century.

- The Book of Dreams recounts the Maccabean revolt (160-140 BC) in the form of an allegorical vision: it can therefore be dated with relative certainty to that period.

- The Epistle and Parables are the most controversial sections: the Apocalypse of the Weeks (cc. 93-94) exists in Aramaic and dates back to the 2nd century BC; the Parables – absent in Qumran – oscillate between 50 BC and 100 AD, depending on whether or not one sees an evangelical influence.

When I speak of “influence,” I am not alluding to plagiarism, but to a cultural environment charged with eschatological expectations: Son of Man, Kingdom, final judgment bounce from Qumran to the Gospels, passing through this late Enoch.

The Watchers, the Giants, and the origin of evil

In the Book of the Watchers, we find a surprising narrative: it is not man who generates evil, but another civilization. Two hundred “watching angels”—guardians, emissaries, soldiers, with roles and hierarchies—decide to descend to Earth, choose women, and unite with them. From these unions, the giants are born, described as powerful and destructive hybrids, causing a degeneration that affects animals, humans, and the entire natural order.

“When the bené Elohim came down and took the daughters of men as wives, the giants (nefilim) were born […] and they devoured the fruit of men’s labor, drank their blood, and brought violence upon animals, reptiles, and fish.”

Genesis (6:1-4) sums it all up in four verses. Enoch, on the other hand, offers names, hierarchies, numbers: two hundred Watchers led by Semyaza, among whom Azazel stands out, the repository of technological knowledge that should not have been shared. Swords, armor, cosmetics, astrology, herbal medicine: a package of knowledge that changes human society and makes it similar (too similar) to that of the Elohim.

Sin, therefore, is not “moral” in the style of catechism; it is an interference of species—genetic and cultural—that breaks the rules of an experiment. At that point, the archangels (Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, Suriel) intervene to clean up the field: the Watchers are imprisoned “in the dark valleys,” the giants are exterminated by the Flood, and humanity is recovered by a mediator, Enoch himself.

The transmission of knowledge as “sin”

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Book of Enoch is that the Watchers, after joining with the women, teach them all kinds of knowledge: metallurgy, astrology, herbal medicine, magic, cosmetics. Azazel, in particular, teaches them how to forge swords and armor; others impart knowledge of spells, astrology, and lunar cycles.

This “gift of knowledge” is perceived as an act of corruption, intolerable to the civilization of the Elohim. And this is where the archangels Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Suriel intervene to restore order, imprison the Watchers, and destroy their children.

We are faced with a radical vision of human history: corruption does not arise from an act of disobedience on the part of man (as in the theology of original sin), but from an external, concrete, material intervention by a superior civilization.

What are we talking about when we talk about “angels”?

One of the most deeply rooted misunderstandings is the word “angel.”

In the Aramaic text we find malʾakhim, “envoys, messengers.” In Greek, angeloi, we find these same individuals with essentially the same characteristics and functions. In my analysis of the Bible, I have shown dozens of passages in which these malʾakhim eat, sweat, get their feet dirty, have to wash themselves, can be physically attacked…

In Enoch, we see them rebelling, lusting, transmitting knowledge in various fields, making mistakes. The picture that emerges is more like that of a colonial power than purely spiritual beings. If we accept this hypothesis for a moment, then the chain of cause and effect becomes plausible: contact, hybridization, technology transfer, corruption, punitive intervention, flood.

Enoch: the patriarch who ‘shuttled back and forth’

The central figure is obviously Enoch, the antediluvian patriarch, who in the Bible (Genesis 5:24) is described with a particular expression: ‘Enoch walked with the Elohim’. The Hebrew verb is used in the hitpael form of the root halach, i.e., ithallech, which means “to go back and forth.” So Enoch literally shuttled between Earth and the seat of the Elohim.

In the Ethiopian text, this activity is clearly described: Enoch observes the Earth and the sky, describes the laws of the stars, the seasons, and the astronomical cycles. He is a privileged witness to a higher knowledge, which will also be transmitted to men, with catastrophic consequences.

In the story, even the Most High – Elyon (Hebrew עליון, “he who is above”) leaves his seat to go to Mount Sinai. But if God is pure spirit, omnipresent and omniscient, what sense does it make to speak of a “seat”? Once again, we are faced with material entities that must descend, move, intervene physically…

Enoch, Noah, and the genealogy of a name

A detail that slips by in the video but deserves two minutes of attention: the patriarch Jared (Gen 5) appears as the son of Mahalalel or, in another tradition, as the son of Enoch. The name derives from the verb yarad, “to descend.” The Ethiopian text notes that the arrival of the Watchers takes place “in the time of Jared” (be-Iared). Some copyists have transformed be-Iared into be-Ardis (Ardis), which would be the name of the mountain on which they descended.

If we return to the verb, the very name of Jared could fix in genealogy the memory of a descent: that of the sons of heaven. This is exactly the kind of clue that philology gives us—a tiny stone on the path, but enough to confirm that tradition preserved, in the fabric of names, traces of events perceived as historical.

Enoch’s “uncomfortable” message for traditional theology

Why did the Book of Enoch disappear from the Roman canon? Because – I feel I can say this without mincing words – it undermines the doctrine of original sin. If evil does not arise from Eve biting an apple, but from higher entities that interfere with man, the theological architecture that justifies the need for redemption by divine grace collapses.

It is no coincidence that the Letter of Jude (vv. 5-7, 14-15) openly quotes Enoch, but in the following centuries the Latin fathers were wary of the text; Tertullian defended it while Augustine avoided it; in the end, the book was placed on the Index, survived in the Coptic liturgy, and only returned through the window thanks to 19th-century Orientalists.

Conclusion

We have exceeded three thousand words and, I believe, have only scratched the surface of this world. In the next articles—and in the next videos—we will follow a clear direction: we will analyze the widespread idea of a single, linear, uninterrupted biblical tradition. Enoch reminds us that the religious history of Israel (and the Near East) is a swamp of competing currents, rival schools, and theological experiments that were aborted or survived in unexpected peripheries.

If we really want to understand the Bible, and not just believe it to be the true word of God, we must allow ourselves the luxury of reading these texts with new eyes, without fear of questioning centuries of catechism.

All this invites us, once again, to re-read ancient texts with an open mind.

The Book of Enoch, which remained canonical only in the Ethiopian tradition, is a valuable tool for understanding how biblical narratives are only part of a much larger and more complex history.

As always, my invitation is the same: “Let’s pretend that…”. Let’s pretend that Enoch really did travel back and forth between Earth and a heavenly abode. Let’s pretend that those Elohim were material beings. And perhaps, only then, will we be able to read these texts for what they probably are: ancient testimonies of encounters, clashes, and transmissions of knowledge that still deeply question us today.

Let’s pretend – and see where the journey takes us.